Blog

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 4: ...

In this series of blogs, I’m emphasizing factors that can have a profound effect on learning but are often left unattended. We all do this. We do it ...

.png?width=1387&height=526&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(61).png)

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 5 - The Post Instruction Phase

By Michael Allen | December 07, 2022 | Custom Learning | 0 Comments

In this series of blogs, I’m emphasizing factors that can have a profound effect on learning but are often left unattended. We all do this. We do it for various reasons, including very pragmatic ones such as the fact that developing good training requires professional attention to the myriad components of a training program. We have much to do. We’re not looking for more.

Recap the Learner's Journey Blog Series (Part 1-4):

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

We leave some important factors on the sidelines because we haven’t typically thought there was anything we could do about them, even if we had the time and energy. And we’ve hoped, perhaps subconsciously, that since we don’t typically concern ourselves with such things as motivations, attitudes, feelings, and worries—nor even prior learning in the preponderance of cases—those factors would care for themselves. They’d just fall in line.

Or not.

While my work focuses on experience-based e-learning (XEL), the associated concepts I’ve been focusing on recently are applicable to all forms of instruction. Differences are only in the manner of implementation. Indeed, the model that most inspires me is that of the personal mentor. I’m reflecting throughout my design work on what I would want a personal mentor to do as I’m learning and what would I do if I were mentoring another person.

SPECIAL NOTE on XEL: Because the term “e‑learning” has come to represent a wide range of training paradigms, including the simple distribution of content slides at one end of a continuum to intelligent simulations with VR near the other, e-learning is no longer descriptive of any specific form of digitally supported learning. The forms of instruction under its umbrella differ in major attributes.

In fact, the same can be said of distance learning as clearly e-learning is a form of distance learning. The horrendous experience families have had with distance learning, which has become a necessity, is, unfortunately, criminalizing the whole continuum of distance learning, including what are powerful, fun, and effective paradigms.

For clarity and to differentiate interactive e-learning that provides authentic digital learning experiences that build skills transferable to real-world performance, we at Allen Interactions are adopting a new term, XEL, for eXperience-based e-learning. It's a form of distance and e-learning for sure, but to just call it e-learning is like calling a Ferrari just a car or an Olympic gold medalist a swimmer.

The Learning Journey

We can think of the process of going from novice to competent, confident, and even joyful performer as a “journey”. You plan ahead, get your mind and body ready, set work aside,

and get started. You expect experiences along the way.

For some journeys, we need a guide to point out things we shouldn’t miss, to know where to step (such as when you climb Dunn’s River Falls in Jamaica, where even with a guide I failed to step in the right place and broke my toe as my bride and I on our honeymoon climbed the rocks hidden by rushing waters), and to help us practice to perfect our performance.

The Learner's Journey is similar to a physical journey in many ways. We need to get ready, organize our mental baggage, set aside time, minimize distractions, set an out-of-office message, and get going.

The Learner's Journey is similar to a physical journey in many ways. We need to get ready, organize our mental baggage, set aside time, minimize distractions, set an out-of-office message, and get going. Suppose we keep notes and photos that recount our experiences for others and even repeat the same or similar journey. In that case, we will even more strongly internalize the lessons delivered by the experiences.

Be a Sherpa for Learner Success

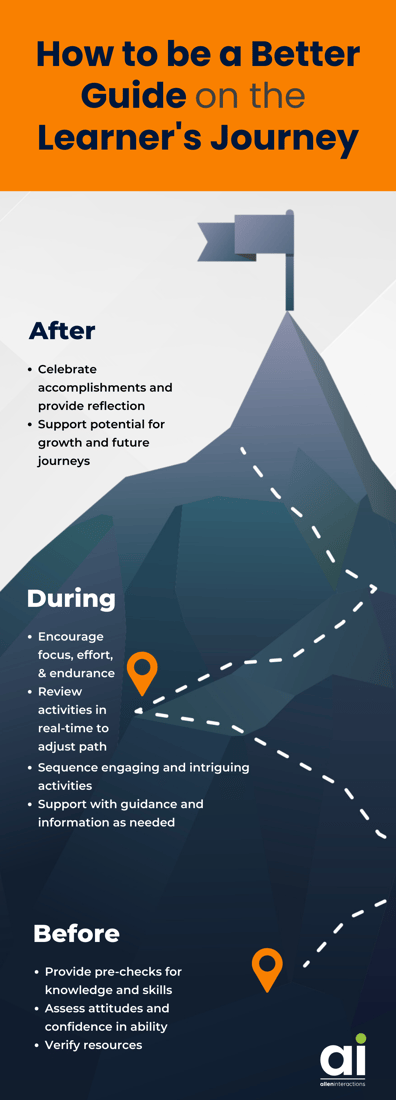

How can we be a great guide for our learners? How do guides help?

Prior to a trip, guides…

- Make sure we’re ready. Climbing Mt. Everest would not be an appropriate experience for someone who has never even tried a climbing wall.

- Assess our limitations and attitudes. For Mr. Everest again, acrophobia, a broken leg, or a person much more interested in hiking would suggest a different excursion.

- Take inventory of our previous experiences and skills. While repetition is powerful, it provides less advancement to those already proficient and potentially takes venturers to the point of boredom or rebellion rather than the intended destination.

- Check our resources. Be sure we have the time and equipment necessary.

During the trip, guides…

- Sequence activities to both intrigue us and keep us engaged.

- Evaluate the need for in-route assistance and appropriate selection of alternative experiences that could come next.

- Support with guidance and information as needed, but not when unneeded.

- Encourage focus, effort, and continuation.

- Review steps, provide feedback, and reward accomplishments.

After the trip, guides…

- Celebrate our accomplishments: congratulate us on a safe and successful journey.

- Support our curiosity: good guides encourage us to keep journeying.

- Provide reflection: recap what we’ve experienced and learned.

- Serve as a referral: ask us to recommend them as a guide to others.

Mastering Mentorship

Mentors continuously observe and ask questions. When errors are made, a good mentor doesn’t just correct them but tries to determine what was the root cause of the error.

them but tries to determine what was the root cause of the error.

My friends at Partners in Leadership (now Culture Partners) offer incredibly important insight. It's a simple notion standing right in front of us, but a notion we pay little head to in training and management.

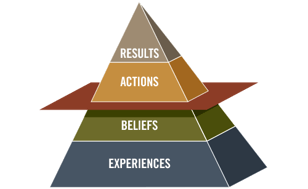

As represented by Culture Partners' Results Pyramid to the right: People act in accordance with their beliefs.

People Act in Accordance With Their Beliefs

It had to be said again. This is why so many management directives fail. Management usually assumes people will act as directed. While a new directive may have a temporary effect if employees believe their current familiar methods are working well or well enough, they will stay with them. They might change temporarily while under observation but find ways to gravitate back to what they had been doing previously. They may, in fact, not even attempt to change.

So, beliefs direct actions. And what determines our beliefs?

Experiences Determine Beliefs

Tracing downward on the Results Pyramid, we see our experiences develop our beliefs and ultimately control our actions. Makes sense. Therefore, what do we want in our training programs? Experiences. This approach differs radically from paradigms that present and test learners, or what I call “tell and test.”

Tell-and-test is what we’ve seen played out in so much of academia for decades. It’s convenient to deliver, fits into fixed periods, and is pretty much what I dealt with as a student until I reached post-graduate work. I remember the most from earlier education in classes where I was doing things. In English class, where I wrote papers and gave speeches. In psychology, I designed, conducted, and analyzed experiments. In shop class, where I made mechanical drawings and then built from them. They all provided experiences under mentorship.

Mentorship Matters

Experience-based learning is so much more effective than various forms of tell-and-test, of which there are many. I’ve advocated a shift to it for a very long time, including in this series of blogs. It makes a huge difference. I’m asking myself if that’s it. Is that all we need to do? It isn’t really that hard, although I admit many people still think it is.

An interesting study by Olivero, Bane, and Kopelman (1997) showed a training program increased productivity by a very respectable 22.4 percent. But when they added coaching, “which included: goal setting, collaborative problem solving, practice, feedback, supervisory involvement, evaluation of end-results, and a public presentation, productivity increased by 88.0 percent, a significantly greater gain compared to training alone.”

In previous blogs, I’ve talked about assessing and being responsive to learners’ affective states.

- What are learners worried about?

- What are learners wondering about?

- How are learners feeling?

These are things mentors and coaches find to be important cues as they decide how best to help learners.

While mentoring is part of the overall process of helping learners reach proficiency as fully and quickly as possible, some of the most important help comes after training. As before, some of the things to be done are very simple yet yield a very positive impact.

Spaced practice

Many training programs offer only enough practice to pass a posttest. Training for a posttest sets learners up for posttest amnesia. Short-term memory can get us through recall and performance events, but if we haven’t fully internalized our abilities, we can lose them faster than we learned them.

It’s very easy, especially in e-learning, to contact a learner multiple times after a training program has concluded to provide more practice. Just knowing this will happen helps learners to internalize their learning more fully. Ideally, the time between each subsequent practice period will increase.

Feedback

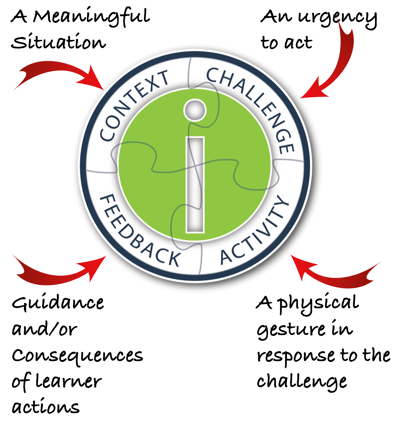

We all know Feedback is important. In the CCAF Model (Context, Challenge, Activity, and Feedback) I find it so powerful, it’s very important to provide the experience of consequence as a component of Feedback. Additional forms of feedback can be extremely valuable as well.

With spaced practice, there’s an opportunity for continued excellence to be acknowledged. Department newsletters can list who is continuing to demonstrate great capabilities. After perhaps 3 or more excellent practice sessions and reaching a level of speed or other perfection, a congratulatory letter from a department head or respected leader can be very meaningful.

A Public Demonstration

A proficient learner may be asked to demonstrate how a task is performed well to a following class of trainees. While surely the instructor can do this or e-learning can as well, having a successful learner demonstrate in person or via Zoom can bolster pride in learning and performing tasks proficiently. It will help strengthen the beliefs of all involved that the new procedures can be learned and learning them brings rewards, satisfaction, and joy.

For many more ideas on providing learner support through the entire learning journey, from preparation and orientation through post-training support, please see Designing Successful e-Learning: Forget What You Know About Instructional Design and Do Something Interesting (Allen, 2007).

References

Allen, M. W. (2007). Designing successful e-learning: Forget what you know about instructional design and do something interesting. Pfeiffer.

Olivero, Gerald & Bane, Denise & Kopelman, Richard. (1997). Executive Coaching as a Transfer of Training Tool: Effects on Productivity in a Public Agency. Public Personnel Management. 26, 461-469.

About the Author: Michael Allen

Go to https://www.alleninteractions.com/bio/dr-michael-allen Michael W. Allen, PhD, has been a pioneer in the e-learning industry since 1970. For decades, Allen has concentrated on defining unique methods of instructional design and development that provide meaningful, memorable, and motivational learning experiences through enhanced cognitive interactivity. He developed the advanced design and development approaches we have used at Allen Interactions for the past three decades, including CCAF-based design and the SAM process for iterative, collaborative development. Michael is a prolific writer, sought-after conference speaker, and recognized industry leader, having written or edited nine books on designing effective e-learning solutions, including his latest edition: Michael Allen’s Guide to e-Learning. He has contributed chapters to textbooks and handbooks published by leading authors and associations.

Comments

Would you like to leave a comment?

Related Blog Posts

.png?width=316&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(59).png)

By: Michael Allen | Dec, 2022

Category: Custom Learning, Dr. Michael Allen

.png?width=316&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(57).png)

Blog

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 2

In this series of blogs, I’m emphasizing factors that can have a profound effect on learning but are often left unattended. We all do this. We do it ...

By: Michael Allen | Feb, 2021

Category: Custom Learning, Dr. Michael Allen

.png?width=316&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(56).png)

Blog

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 1

In this series of blogs, I’m emphasizing factors that can have a profound effect on learning but are often left unattended. We all do this. We do it ...

By: Michael Allen | Feb, 2021

Category: Custom Learning, Dr. Michael Allen