Blog

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 3: Getting ...

I’m beginning to share some practical approaches to designing components of the learner’s journey, including not only the content and the experience ...

.png?width=1387&height=526&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(59).png)

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 4: Practical Design Approaches for Experience-based Learning

By Michael Allen | December 01, 2022 | Custom Learning | 0 Comments

I’m beginning to share some practical approaches to designing components of the learner’s journey, including not only the content and the experience of learning new skills, but also of addressing the affective component of the journey.

Addressing the primary components of the learning journey, how we address them, and even the order in which we address them define Instructional Design 3.0. We’ve got a lot to cover! But we’ll do it in small steps.

Catch Up on the Learner's Journey Blog Series

The Essential Components of Experience-Based Learning

Experienced-based learning emphasizes the practice of learning outcome skills in actual contexts or contexts simulated as closely and cost-effectively as possible. Andresen, Boud, and Choen (2000) provide a list of general criteria for experience-based learning, applicable whether a digital platform is in use or not. The authors state that for learning to be truly experiential, the following attributes are necessary in some combination.

- The goal of experience-based learning involves something personally significant or meaningful to the students.

- Students should be personally engaged.

- Reflective thought and opportunities for students to write or discuss their experiences should be ongoing throughout the process.

- The whole person is involved, meaning not just their intellect but also their senses, their feelings, and their personalities.

- Students should be recognized for prior learning they bring into the process.

- Teachers need to establish a sense of trust, respect, openness, and concern for the well-being of the students.

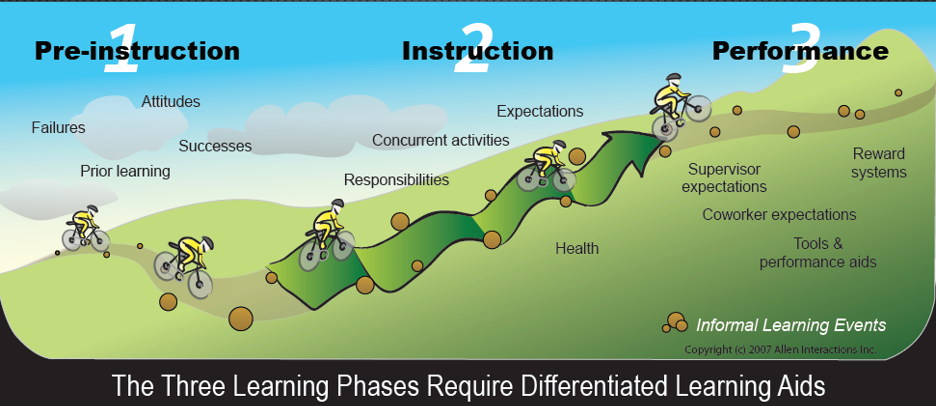

In my book, Designing Successful e-Learning: Forget What You Know About Instructional Design and Do Something Interesting (Allen, 2007), I’ve observed that we all too often ignore learner preparation before we jump into instruction. In addition, we often ignore the support needed to assure the successful transference of new skills to long-term application.

Looking at the whole of the learner’s journey, we must first consider past successes and failures, prior learning, and attitudes. We’ll take up Phases 2 and 3 in later blogs, but note here that many factors affect both learning and performance which must also be taken into account for the most effective training and performance practices.

Learner-First Design

As I suggested in the first blog in the series, it may be most effective for us to begin our work in experienced-based learning by addressing the learner first, followed later by addressing the learning experience, and then finally addressing the content. This is quite the reverse of tradition and perhaps even logic, but the logic conundrum occurs only if you suppose learning is primarily about communicating the content you want to teach as opposed to helping people grow their insights and skills. My focus is always on helping people grow their insights and skills. And that happens best (and only) through having just the right experiences at the right time.

Practicality

I advocate doing what it takes to create effective learning. It’s not a win for any organization to minimize training development costs at the risk of putting people through time-wasting, and ineffective training (at potentially great costs and lost opportunities). At the same time, I try desperately to find affordable, practical methods of producing great training. I'm going to share a variety of techniques. Some are very simple, inexpensive, and quick. Others are more sophisticated and worth the effort. However, all techniques are designed to create far more effective learning experiences than we typically see today.

Example 1: A Cool Approach to Addressing Learner Concerns

Before we look at different affective attributes individually, one technique has captured my attention and has great appeal. This technique calls for some advanced preparation that isn’t always practical, but it’s worth considering and reaching for wherever possible, even if some compromises are necessary. It takes advantage of the digital platform and introduces powerful learning support that hasn’t been possible previously.

“You Ain’t Never Had a Friend Like Me”

As I’ve noted, in many aspects, a personal mentor is my gold standard, although sometimes I’d like even more help than a mentor could provide. Maybe a genie could just do the task for me!

As Aladdin’s genie sang...

Life is your restaurant

And I'm your maitre d'

Come, whisper to me whatever it is you want

You ain't never had a friend like me[1]

Providing learners the comfort of a friend, perhaps in the form of another learner ready to share experiences, seems like not only the obvious thing to do but also a great thing to do. It hasn’t often been practical, but now there are many ways to do this.

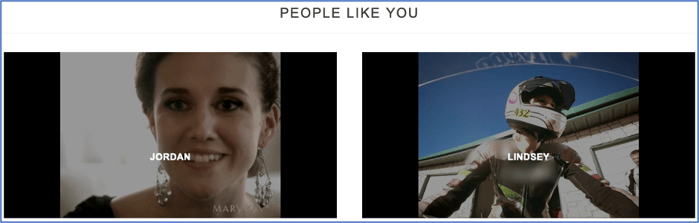

One fantastic example is what Mary Kay Cosmetics did with e-learning to onboard new beauty consultants (who are or must become entrepreneurs and business owners to succeed and reach their personal goals).

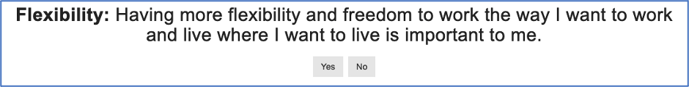

In this implementation, designed and built by Allen Interactions, an interactive e-learning program asks aspiring beauty consultants about their feelings, worries, and aspirations. A series of questions are presented including questions such as this one concerning the reasons why the learner is considering becoming a Mary Kay Beauty Consultant:

Depending on their answers, learners are given access to videos of people who answered exactly the same way they did.

As learners continue to answer questions, a personal library of videos builds up, so learners can play and return to the selected content whenever it seems helpful and relevant. Learners discover how others achieved their goals, overcame their fears and hesitations, and became successful. Hearing personal stories from others has more affective impact than hearing a corporate sales pitch, especially with the stories being selected based on expressed concerns and aspirations.

Example 2: What’s Your Story?

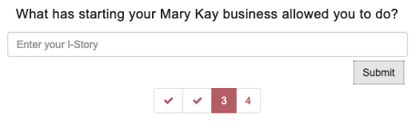

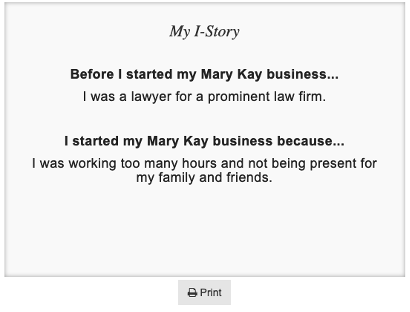

I have another example from Mary Kay Cosmetics. In contrast to Example 1, which necessitates extra work to create (and is well worth it), this technique takes very little preparation, is easily implemented, and sets learners on a good learning trajectory from the start. It provides a true sense of personalization that experience-based learning programs can provide so easily.

Learners are asked to build their own “story,” prompted by a series of questions. A wide range of questions can be effective depending on what would be appropriate for your learning population, the instructional content, and the targeted outcomes. Here is one of the questions Mary Kay asked:

Building your “I-Story” sets forth a personal mission and reason for learning more—contrasting very much from the typical instructor’s admonition saying, in effect, “The reason you are in this class is...” Well, the “reason” might be whatever the instructor suggests. But we, as learners, have our own reasons. Perhaps we’re taking the training only because it’s a requirement just to keep our job. Most likely, however, as we answer questions to write out our journey, we would start to think, “If I have to spend the time, perhaps I should make the most of the situation.” Nobody wants to waste their time. So, your story will help you be constructive and plan for the success you care about.

Purposeful learning is both more enjoyable and more effective as learners are more likely to make the effort needed to get the most out of the experience.

Example 3: How Can We Help You?

Because we would like to partner with our learners and help them along their journey, it would be helpful to ask some questions with structured responses that we can act on.

Here are some examples:

|

Question |

Response Choice |

Feedback/Action |

|

How eager are you to learn how to use our new CRM system? |

I feel I'm already proficient in the CRM. |

"Hey, that's great. Is it okay if we throw some challenges at you to see if you can meet them? We'll help you out if you struggle at all." |

|

I'm good at figuring out how to use new software. I can just ask if I run into problems. |

"It's really rewarding to take on new challenges, apply your experience and smarts, and learn how things work. It's kind of like playing a game, isn't it? Okay, go for it! We'll help you out whenever you ask for a hint or more aids." |

|

|

Once I get comfortable with a system, I'm rock solid on it. But I'm not a quick learner of new ones. |

"No problem. Thanks for letting us know. Our only aim is for you to get very comfortable with the system by developing a strong knowledge of the system and confidence through practice." |

|

|

I'm excited about this course! |

"Hey! It's designed to help you build valuable skills and be fun while you're learning. Welcome aboard! We'll check back later to see how it's going for you." |

|

|

What are your thoughts about taking this course online? Please choose all that apply. |

I'm taking it online because it's only offered online. |

"There are some great advantages of online courses. One of them is that we can tailor it just for you. Let's give it a try. We'll ask you again what you think after you've been studying for a bit." |

|

I prefer online courses only for the schedule convenience. |

"You can start and stop when you need to as well as go fast or take your time. Let's make it work for you." |

|

|

I don't like online courses. |

"Online courses aren't all alike. We know some are tedious. We hope this one will stand out and become one of your favorite courses. Please let us know how it's going via the feedback options provided throughout." |

|

|

I like online courses because I can go fast and don't have to wait for other students. |

"Yup! We encourage you to speed up and slow down as is best for you. Be sure to practice enough to build rock-solid confidence in your skills. Enjoy!" |

|

| What worries do you have about taking this course? |

That I'll get confused and won't have anyone to ask or help me. |

"We sure hope that won't happen. We have made provisions for you to get help when you need it. Look for the HELP buttons available throughout the course." |

|

That it's going to be hard. |

"A little challenge can be fun, especially when you find you're quite up to the task. But as an online course, we've programmed its ability to adjust challenge levels and help you as needed. Let's make sure that that concern evaporates as you work through the course." |

|

|

That my supervisor will see my mistakes. |

"Mistakes are a great way to learn. At some points in the course, we will invite you to make mistakes so you won’t miss the opportunity to see what happens. Have no worries about mistakes, whether made unintentionally or not! It’s all part of a learning experience." |

|

|

That I’ll spend a lot of time on it and learn very little if anything. |

“The course is designed to be adaptive. If you’re already proficient in the skills being taught, you’ll be able to breeze through quickly.” |

|

|

That it will be boring, boring, boring. |

“Oh, we hope not. We don’t like boring courses either. Where we could, we’ve used a game-like structure to make this course both fun and effective. It will help you to gain and practice valuable skills while, we hope, having fun. Let’s see how it works for you.” |

|

|

I don’t have worries about it. |

“That’s great! You really shouldn’t. We expect this will be a fun and effective learning experience for you.” |

Just asking and giving supportive responses can help learners get started on the right foot. We want them to know we care about them as individuals and want to provide a learning experience that is best for them.

While we could just state that we care and then deliver a standard program, that’s probably the worst thing to do. It’s far more effective to first ask learners what they are feeling, what they are thinking about, and what worries they have and:

- Respond with individual messages to point out the special characteristics of the program

- The harder part, create a learning experience that actually responds to their feelings, thoughts, and worries.

Example 4: Do You Know What You Know?

In my research I had the good fortune to conduct when I was at The Ohio State University, we were using an early instructional system based on IBM’s Coursewriter system—an early system for interactive digital instruction that had pretty great capabilities even in the 1960s! In conjunction with a national demonstration center for advanced instructional methods, funded by the National Science Foundation, we built a system for Student-Initiated Repeatable Testing (SIRT). It was delivered via computer terminals in a large self-study center where students had access to a very large variety of learning resources and were to learn mostly on their own without attending formal classes. The only requirement was taking a final exam, which determined their course grade.

To help students decide how best to use their time, at any time and as often as desired, students could use a SIRT terminal to test their knowledge of biology—the content taught in the center. Having a large repository of test questions to draw from, unique tests were generated for each student whenever the student requested a test. When a student answered a question incorrectly, feedback indicated this but did not reveal the correct answer. Rather, at the end of the test, algorithms looked at the pattern of responses to determine learning needs and suggest learning activities and resources that would likely be most helpful. Nothing too advanced was prescribed and neither was anything too basic for the individual.

The program was very successful but raised the question of whether some students might just be good at guessing correct answers in multiple-choice questions. Some students tried the tactic of taking tests over and over again in hopes of deducing the right answers. But as students discovered and we were relieved to find out ourselves, the tactic took more time and effort than studying to learn the material. Repeated tests without interleaved learning turned out to take extra time and effort. Students abandoned the practice on their own. But even with randomly selected questions (from stratified pools), we still wondered about whether good guessing might be masquerading as knowledge.

Targeting Learner Confidence as an Instructional Goal

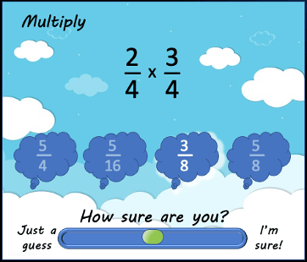

Continuing our exploration, we decided to enhance the system by assessing learner confidence. After answering each question and before providing learners any knowledge of results, the SIRT system asked learners how confident they were that they’d been given the right answer. There was no penalty given for admitting it was a guess. We just wanted the learner’s assessment.

But then we enhanced the system one more time by making two significant changes:

- First, students would not have to take the final exam if, before the date of the exam, they had achieved sufficiently high scores (96%) on all topics in the course. This was a big and popular incentive, of course. The student had completed the course, no matter when it happened during the school term, and a grade of A would be awarded, subject to the second condition added (see below).

- Second, students couldn’t achieve our mastery criteria and bypass the final exam unless they had 1) high confidence with their correct responses and 2) indicated low confidence or even a guess when they made the occasional error.

In other words, confidence had to be highly correlated with competency. You had to know what you knew and what it was you didn’t know.

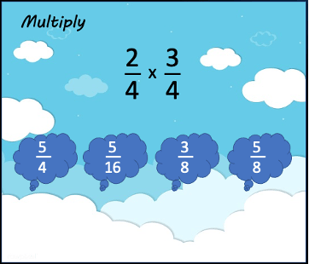

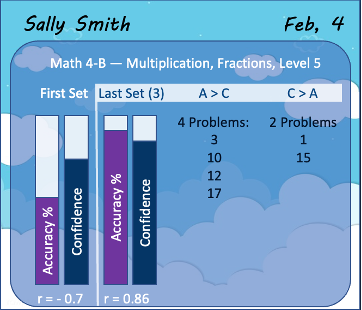

Here’s an example of another application of this approach, this time in math, multiplying fractions:

Gathering performance data as learners work, which we must always do to provide optimal learning experiences, informs the course’s branching strategy. Let’s look at what’s possible from this very simple addition of polling for confidence.

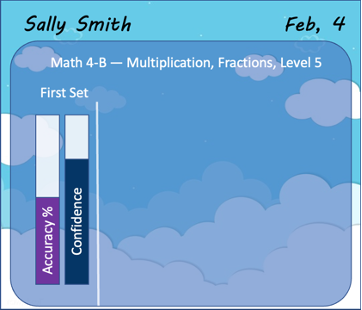

Sally has completed one set of exercises, just her first. Her confidence exceeds her accuracy by a significant amount.

This table compares Sally’s performance on her first set of exercises (the two bars on the left) with her last set (the two bars on the right). In total, she has now completed 3 sets of exercises, but we’re just comparing the first and last performances.

Note that confidence and accuracy have become much better correlated overall. But the data are more prescriptive than just that important measure of progress; they also call out specific exercises in which there were competency and accuracy discrepancies.

Sally’s confidence on exercise problems #3, 10, 12, and 17 was lower than her accuracy. Some practice on these exact problems and similar ones could help build her performance confidence.

Her confidence on problems #1 and 15 is high, but that’s not a good thing because she’s confident that her incorrect responses are correct. Here, some explicit instruction relating to why incorrect responses are incorrect and correct responses are correct is warranted and should be helpful.

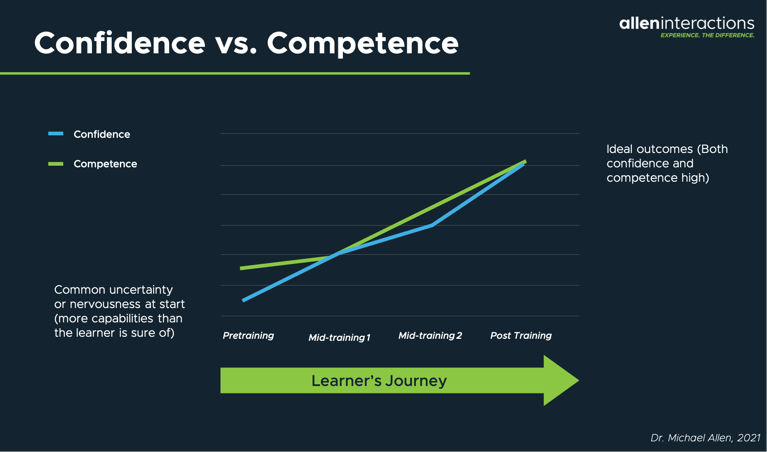

The outcomes we always seek are high competency with matching and correlating confidence as shown in the following graph. By assessing both at the start of training and at a checkpoint along the journey, we can adjust the learning experience in optimal ways.

Final Words

I hope these ideas and few examples inspire you to focus first on your learners.

- How might they be feeling?

- What are they thinking?

- What might they be worried about?

As you consider these questions, it’s very unlikely you will conclude all your learners are alike in these dimensions. If you conclude, as I have, that these differences are influential in the learning outcomes any program can achieve, the question to consider then is, how can we adjust the learning experience to mitigate the negative and distracting influences while we bolster the positive and helpful ones. I hope these examples confirm that it’s possible to find practical, cost-effective means.

Read Part 5

References

[1] Alan Menken, Howard Ashman. Friend Like Me.

Allen, M. W. (2007). Designing successful e-learning: forget what you know about instructional design and do something interesting. John Wiley & Sons.

Andresen, L. (2000). In Foley, G., Understanding Adult Education and Training, 2nd ed., pp. 225-239. Allen and Unwin.

About the Author: Michael Allen

Go to https://www.alleninteractions.com/bio/dr-michael-allen Michael W. Allen, PhD, has been a pioneer in the e-learning industry since 1970. For decades, Allen has concentrated on defining unique methods of instructional design and development that provide meaningful, memorable, and motivational learning experiences through enhanced cognitive interactivity. He developed the advanced design and development approaches we have used at Allen Interactions for the past three decades, including CCAF-based design and the SAM process for iterative, collaborative development. Michael is a prolific writer, sought-after conference speaker, and recognized industry leader, having written or edited nine books on designing effective e-learning solutions, including his latest edition: Michael Allen’s Guide to e-Learning. He has contributed chapters to textbooks and handbooks published by leading authors and associations.

Comments

Would you like to leave a comment?

Related Blog Posts

.png?width=316&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(58).png)

By: Michael Allen | Mar, 2021

Category: Custom Learning, Dr. Michael Allen

.png?width=316&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(61).png)

Blog

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 5 - The ...

I’m beginning to share some practical approaches to designing components of the learner’s journey, including not only the content and the experience ...

By: Michael Allen | Dec, 2022

Category: Custom Learning, Dr. Michael Allen

.png?width=316&name=2023%20Blog%20Covers%20and%20In-Line%20Graphics%20(57).png)

Blog

Instructional Design 3.0: Designing the Learner’s Journey - Part 2

I’m beginning to share some practical approaches to designing components of the learner’s journey, including not only the content and the experience ...

By: Michael Allen | Feb, 2021

Category: Custom Learning, Dr. Michael Allen