Blog

5 Instructional Design Insights from The Marshmallow Test: Part I

By Edmond Manning, Senior Instructional Strategist Welcome back! In my last blog, I introduced the 2014 book, The Marshmallow Test by researcher ...

5 Instructional Design Insights from The Marshmallow Test: Part 2

By Edmond Manning | June 08, 2017 | Custom Learning | 0 Comments

By Edmond Manning, Senior Instructional Strategist

By Edmond Manning, Senior Instructional Strategist

In my last blog, I introduced the 2014 book, The Marshmallow Test by researcher Walter Mischel. His life’s work reveals insights collected from decades of research on willpower and its relationship to decision-making. While this book was not written for instructional designers, the implications for the affective domain are fascinating.

My previous blog addressed the power of “hot and cold focus” in decision-making moments as well as how we might use those insights in creating training experiences. Now, I’d like to share insights equally applicable to the world of training.

#4 – Believing in the consequences influences behavior

Mischel reports some children simply didn’t believe that they would get a treat if they waited for it. Their patience was tested by researchers staying away from the room for long periods of time, and running variations of the experiment, like returning, rewarding the child, and then promising a greater reward for another demonstration of patience, and leaving for a longer period of time.

Their patience was tested by researchers staying away from the room for long periods of time, and running variations of the experiment, like returning, rewarding the child, and then promising a greater reward for another demonstration of patience, and leaving for a longer period of time.

(Knowing myself, I would've popped that marshmallow in my chubby cheeks before the door had even closed.)

Children who believed in the positive consequences, waited.

They had faith.

Faith can be increased or decreased by hot/cold focus, removing temptations, ability to envision success, executive function, and many other variables. Regardless of how to address these variables, how often do you stop and consider ‘faith” as a crucial ingredient to your instructional design?

On another day, the cold logical part of my brain could easily argue that “faith” has no place in the science of instructional design. But faith does have a place for our learners. We tell them, “believe in these consequences, for they might come to pass.” But will those consequences come true? In training, have you ever read, “Do this or you could be fired?” I have. It makes me roll my eyes.

Mischel’s observations about faith makes me ask these questions about training:

- Have I given them any reason to put faith in this training? Or, the possible outcomes from completing it?

- Do learners believe in these consequences or are they wise to our usual ho-hum “training talk?”

- What faith does my client put into their learners, and does that lack of faith create limitations to expecting adequate performance? I’ve certainly witnessed clients trash-talk their learners, and how “stupid” they are. Shocking as it is when I have heard this, I immediately recognize the limitations this client will have in recognizing a learning solution that respects their learners’ intelligence.

So, maybe the concept of faith has a place in instructional design after all.

#5 – Current Self and Future Self

Very-much related to the concept of faith in consequences are the ideas of Current Self and Future Self.

Mischel’s studies correlate children’s ability to wait for the return of researchers to success later in life. Those who can delay their gratification tend to work toward long-term goals. One of the children summarized Mischel’s body of research and statistical correlation this way: “I didn’t eat it because I kept imagining two marshmallows into my mouth at the same time.”

(In a spirit of transparency, I often imagine two marshmallows in my mouth as well.)

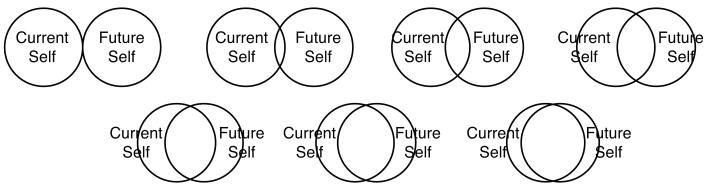

Using many more words, Mischel illuminates his conclusion: the extent to which your Current Self can relate to your Future Self influences how much Current Self acts in Future Self’s best interests.

For example, if you want a loved one to lose 200 pounds, you might entice them by praising how “great it will feel” to wear skimpy clothes to the beach, how they will jog with ease, etc. However, that Future Self might be too distant and unrelatable. You might do better relating a Future Self who loses 25 pounds, someone who goes up and down stairs with more ease. THAT Future Self might be close enough to be more relatable.

(In a great anecdote, Mischel discusses how twenty-somethings have a difficult time planning for retirement because that Future Self is barely imaginable. This certainly explains why I did so little with my first 401K when I was 27, and my near-panic now, as I’m almost 50.)

In instructional design, I often witness Instructional Designers create a Future Learner as a motivation strategy, too:

- “If you do X, you’ll finish your work faster!”

- “If you do Y, your customers will be happy.”

- “If you do Z, you’ll make a lot more commission!”

Big promises.

These big promises ask Current Learner to stay motivated on the off-chance Future Self comes to pass. But can you really promise happier customers? Can you promise that finishing work faster benefits the employee (other than more time for more work)?

It’s no wonder learners are skeptical of training. They can’t identify with the Future Self. And, we rarely paint a compelling enough picture of what that Future Self might look like.

If you want Current Learner to feel success, define tangible, relatable success for Future Self. The key is relatable. Instead of promising “a lot more commissions,” break down how commission is impacted, and show how, over the course of a month, that could be an extra $200. You may think the bigger carrot of “thousands in commissions” is a better enticement… but maybe that Future Self seems too far off to be achieved.

Caption: The more Current Self can relate to Future Self (i.e. more overlap), the greater the odds of Current Self acting in Future Self’s best interests.

Consider the Affect

The science of instructional design analyzes performance in terms of logic: skill hierarchy and observable verbs in our performance objectives.

Logic is good. We like logic.

But we often exclude the possibility (or at least fail to include the possibility) that learners aren’t performing as expected because they don’t want to—that their behavior is an act of willfulness as much as it is information-based.

When considering training solutions (and even front-end analysis), consider the power of the affective domain and how it influences our decisions. Use hot and cold focus to your advantage. Consider the Future Self and Executive functions. Make sure consequences are relatable and realistic. Any of these strategies could make a stale learning event more Meaningful, Memorable, and Motivating.

CLICK TO TWEET:

About the Author: Edmond Manning

Edmond Manning, senior instructional designer for Allen Interactions, has more than 20 years designing interactive e-learning experiences on instructional topics including: software simulation, medical ethics, supervisory skills, and selling/presentation skills, and gosh, a whole bunch of others. He has helped mentor and grow e-learning departments, worked as a business consultant, independent contractor, and instructed the ATD e-Learning Instructional Design Certificate Program for more than a decade. Edmond has a master's degree from Northern Illinois University in instructional technology.

Comments

Would you like to leave a comment?

Related Blog Posts

By: Edmond Manning | Jun, 2017

Category: Custom Learning

Blog

11 Instructional Design Truths According to Cat .gifs

By Edmond Manning, Senior Instructional Strategist Welcome back! In my last blog, I introduced the 2014 book, The Marshmallow Test by researcher ...

By: Edmond Manning | Oct, 2019

Category: Custom Learning

Blog

Pokémon Go: 3 Lessons for Instructional Designers

By Edmond Manning, Senior Instructional Strategist Welcome back! In my last blog, I introduced the 2014 book, The Marshmallow Test by researcher ...

By: Edmond Manning | Jul, 2016

Category: Custom Learning