Blog

Three Guidelines for Meaningful Microlearning

Microlearning has been a mainstage presence in L&D for a while now. When the term “microlearning” first appeared on the scene, a lot of the talk ...

.png?width=1387&height=526&name=Services%20-%204%20Principles%20for%20Next-Level%20Microlearning%20(1).png)

4 Principles for Next-Level Microlearning

By Ellen Burns-Johnson & Brent Gwisdalla | May 18, 2021 | Custom Learning | 1 Comment

Microlearning has been a mainstage presence in L&D for a while now. When the term “microlearning” first appeared on the scene, a lot of the talk about the approach revolved around slicing up Big Content into smaller content. The thinking was that learners liked small content more—it fits more easily into a learner’s workday, and small pieces of content are more easily consumed, considered, and understood.

"Big Content"

These days, learning designers are encouraged to take a more sophisticated, goal-oriented, and learner-centered approach to microlearning design. Rather than running a long e-learning course through a Bullet Blender, resulting in a sippable version of the material, designers are encouraged to prepare each “unit” of microlearning carefully and purposefully.

I’ve always thought of microlearning like tapas; each dish is small but memorable on its own. A single small plate can be consumed with just a few bites, but when combined with other dishes, it makes for a pleasant meal.

"Like a tapas dish, each microlearning lesson is small but carefully crafted. And hopefully delicious."

You can see examples of thoughtfully-designed microlearning everywhere these days. You’ll find microlearning design in consumer apps, organizational learning platforms, education sites, and more. Microlearning has evolved. Our ideas about what makes for good microlearning, and what it takes to create it, have evolved along with it. We thought it would be a helpful exercise to revisit our thinking on microlearning in a new series of blog posts, starting with this one.

Microlearning is evolving! Source

Like always, we find it more helpful to describe learning design in terms of the learner’s experience, not according to the structure of the content (though that is important, too). Brent and I got on Zoom and came up with four principles for designing “next level” microlearning.

Four Principles for Next-Level Microlearning:

- It has to be short.

- Make it focused and curated.

- Each lesson should stand on its own.

- Make it convenient and referenceable.

Principle 1: It has to be short.

Okay, this one’s easy. Microlearning has always been synonymous with “short.” Any debate on this point has been about how one defines “short.” We generally think of a single unit of microlearning as being about 5-10 minutes long, but really, any debate about the proper length of a microlearning lesson is missing the point. What one person gets done in two minutes might take the next person eight minutes, and those differences are okay. Time-sensitivity is the foundation of this principle.

The ideal length of a given microlearning lesson depends on the goals of your program and the needs of your learners. What’s important is how the learning “event” fits into the learner’s day or workflow. It should be as seamless as possible. Keep in mind that a learner might choose to complete microlearning in various ways, depending on the structure of their day or week.

Consider how I use Duolingo, the language-learning app:

- 8:00 AM: I sit at the table and finish a lesson or two on my phone while eating breakfast. It takes me about five minutes to do a single lesson.

- 11:30 AM: During short breaks in the workday, I sometimes pull up the Duolingo web app to zip through another lesson or two.

- 2:00 PM: One of the ways I’ve been trying to help out during this pandemic is by donating blood every few weeks. (You can, too!) Sometimes I do a lesson on Duolingo while I’m in the waiting room for my donation appointment.

- 9:30 PM: I almost always do a focused study session before bed. This session is more intense, and I’ll usually complete four to five lessons over 20 minutes or so.

Duo, the Duolingo mascot, will make you feel very guilty if you don’t practice each day.

Microlearning doesn’t demand long periods of sustained focus from the learner. Each lesson is short because it anticipates the learner will frequently step away from the course, although the learner can typically choose to engage with the material differently if they want to. The focused study period I described above, when I sit down to complete several Duolingo lessons one after the other, is an example of this alternate approach.

Principle 2: Make it focused and curated.

Focus is important no matter what type of learning you’re designing, but it’s especially important for microlearning. The learner only has a few minutes, but they expect to accomplish something Meaningful in that time. As designers, we need to meet that expectation.

To make each microlearning lesson Meaningful, every lesson should be focused on one thing. It can be a complete idea or a discernible part of a larger picture. The learner needs to “get” the gist of something, whether that be exploring a concept, trying a process, or practicing a skill. Moreover, the lesson is also curated so that it can be experienced quickly, efficiently, and pleasantly.

Learners have things to do, so they want your microlearning to get right to the point. Source

Curation involves designing the learning experience so that it is valuable for the learner. In a lesson that is well-curated, the learner knows what they’re after, they know they can get it done within the lesson, and they know how the “gist” of the lesson is relevant to their real life.

Curation is important for two reasons:

- Each well-curated lesson makes the learner more likely to return for the next lesson.

- If a lesson is well-curated, learners are more inclined to use that lesson as a reference.

Poorly curated learning experiences are quickly forgotten and discarded. Learners won’t bother returning to a poorly curated lesson, even if they need the information. They’ll just go with what they can remember, even if they suspect their memory of the material is incomplete.

Principle 3: Each lesson should stand on its own.

Each “unit” of microlearning—we call these lessons—should provide some value. Each lesson can stand on its own; if the learner only has time to complete one lesson, they can still feel a legitimate sense of progress. The lessons can then build on each other.

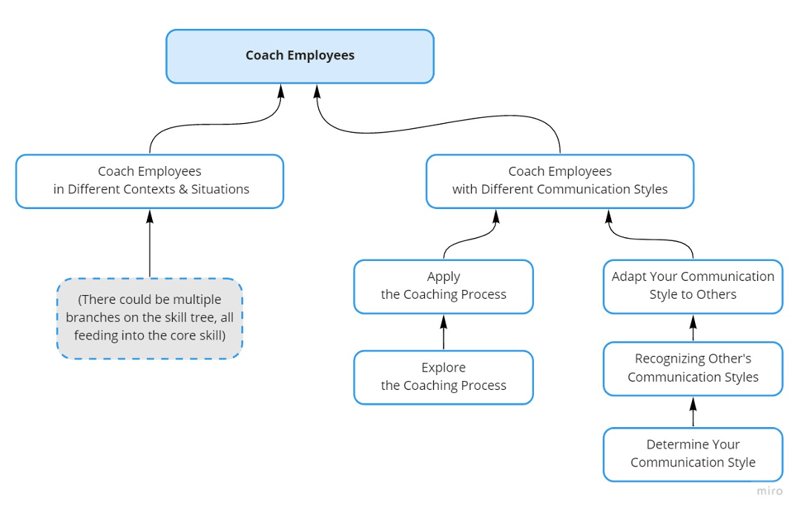

Skills hierarchies or skill trees are a useful tool in constructing courses this way. Here’s a tree that resembles a portion of a coaching course we recently created for managers and leaders at a financial services company:

The core skill, “Coach Employees,” is too complex to be taught through a single microlearning lesson. But by analyzing the foundational skills that enable one to coach others successfully, we can break up instruction into smaller chunks.

Here’s how this small skill tree could be mapped to a curriculum in which each lesson is designed as microlearning:

|

Module Name |

Lesson Name |

Lesson Description |

|

The Coaching Process |

Explore the Coaching Process |

Sorting exercise (5-10 minutes) |

|

Apply the Coaching Process |

5 mini-scenarios, 1-2 minutes each (5-10 minutes total) |

|

|

Communication Styles |

What’s Your Communication Style? |

Questionnaire (3-5 minutes) |

|

Identifying Communication Styles |

5 mini-scenarios with follow-up analysis questions, 1 minute each (3-5 minutes total) |

|

|

Adapting Your Communication Style |

5 simulated conversation exchanges w/ video, 1-2 minutes each (5-10 minutes total) |

|

|

Coaching Practice |

Coaching Scenario 1: Jared |

One 5 to 10-minute simulated conversation; employee has communication style A |

|

Coaching Scenario 2: Aria |

One 5 to 10-minute simulated conversation; employee has communication style B |

|

|

Coaching Scenario 3: Susan |

One 5 to 10-minute simulated conversation; employee has communication style C |

Each lesson feeds into the target performance (Coaching Employees) by focusing on a single concept, introducing a new skill, or providing practice opportunities.

Principle 4: Make it convenient and referenceable.

Have you ever had to jumpstart a car? Do you remember how to do it?

I rarely find myself with a dead car battery, but it happened once this winter when temperatures in Minnesota reached -20°F. I was pretty confident that I remembered how to connect the cables without causing electrical chaos, but I wasn’t certain. I went to YouTube, found a 60-second tutorial video, and got right back to work on jumping the car. It started right up, and I didn’t burn anything. (The weather got warmer, too!)

In this situation, I relied on performance support to fill in the gaps in my memory. Sure, I had learned how to jumpstart a car from my dad when I was a teenager, but I hadn’t practiced the skill frequently enough in subsequent years to make it stick. Skills require maintenance to stay clear in a person’s memory.

“Oh, I see. The red cable goes on first.”

Of course, not every skill is worth ongoing, regular practice. This is the strategic value of performance support. It’s valuable to experienced practitioners who come across a situation that happens infrequently. It’s also valuable to new learners who are just beginning to apply a new skill on their own—they haven’t practiced it enough to make it stick.

When designed thoughtfully, microlearning can serve double-duty as a learning experience and as performance support. This requires that designers create the curriculum in a way that is mindful beyond the initial experience.

One of Allen Interactions’ most award-winning microlearning programs was created as onboarding for Mary Kay consultants. We created the course so that once a learner has loaded it, they’re only a few clicks away from the information they need. Each lesson was easily accessible and usable on any device—useful for consultants on the go. Also, each lesson was curated so that learners would enjoy returning to lessons to reinforce their knowledge and hone their abilities.

We received great feedback from learners who, after completing the curriculum the first time, revisited individual lessons to refresh their knowledge and skills at the moment of need. These new beauty consultants would arrive at an appointment a little bit early and spend ten minutes reviewing lessons on their phone while sitting in their car. That’s smart learning and smart design.

You can read more about the Mary Kay curriculum here.

Wrap-Up

Microlearning isn’t new, but as an industry, we’ve experimented with it and learned a lot about it over the past few years. If you’ve incorporated it into your organization’s training, think about how it works for learners. Does it embody these four principles? If not, maybe it’s time to take it to the next level.

Download e-book now to explore the basics of microlearning design and get foundational knowledge on implementing microlearning!

About the Author: Ellen Burns-Johnson & Brent Gwisdalla

About Ellen Burns-Johnson: Ellen has crafted the instructional strategy and learning experience design for dozens of initiatives, including such diverse topics as hospitality software, elder abuse prevention, corporate compliance, early childhood classroom safety, and medical adhesives. Her clients have included nonprofits, government agencies and multiple Fortune 500 companies. A highly collaborative person, Ellen delights in bringing people together to tackle big learning challenges. Her e-learning experiences have won multiple awards for interactivity and game-based design. About Brent Gwisdalla: Brent Gwisdalla is a Studio Executive and Senior Learning Experience Strategist for Allen Interactions. He has architected countless learning experiences and led projects across a broad spectrum of content areas. For over 25 years, Brent has worked in all phases of instructional design, talent development, e-Learning, and blended training solutions using almost every media imaginable along the way. He holds a master’s degree in instructional design from Western Michigan University and is one of five instructors teaching the e-Learning Instructional Design Certificate program for the Allen Academy. Brent has published articles on instructional design in industry journals and is a visiting lecturer on training and performance management at the WP Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. An insatiable learner himself, Brent is fascinated by brain science, human development, and behavioral psychology.

Comments

Great principles that you put there! It also makes sense as people nowadays have lesser attention span.

Would you like to leave a comment?

Related Blog Posts

By: Ellen Burns-Johnson & Brent Gwisdalla | Mar, 2017

Category: Custom Learning

Blog

Microlearning: Overcoming 4 Assumptions

Microlearning has been a mainstage presence in L&D for a while now. When the term “microlearning” first appeared on the scene, a lot of the talk ...

By: Ellen Burns-Johnson & Brent Gwisdalla | Jun, 2017

Category: Custom Learning

Blog

No Couch Potatoes: A Case for Making Training ACTIVE

Microlearning has been a mainstage presence in L&D for a while now. When the term “microlearning” first appeared on the scene, a lot of the talk ...

By: Ellen Burns-Johnson & Brent Gwisdalla | Aug, 2014

Category: Custom Learning

Elina Lim

6/2/2021, 12:26 AM