Blog

Dear Designer: What Type of ID Are You?

By Ellen Burns-Johnson, Instructional Designer / @EllenBJohnson The Big Short is a recently released dark comedy that explores the 2008 financial ...

Three Solid Instructional Design Principles in The Big Short

By Ellen Burns-Johnson | January 19, 2016 | Custom Learning | 0 Comments

By Ellen Burns-Johnson, Instructional Designer / @EllenBJohnson

-1.png?width=125&name=Ellen(250)-1.png) The Big Short is a recently released dark comedy that explores the 2008 financial crisis. It’s nominated for several awards in the upcoming Oscars, and has garnered significant attention for its success in communicating tricky financial concepts to a general audience. Steve Carell, who co-starred in the film, offered this assessment:

The Big Short is a recently released dark comedy that explores the 2008 financial crisis. It’s nominated for several awards in the upcoming Oscars, and has garnered significant attention for its success in communicating tricky financial concepts to a general audience. Steve Carell, who co-starred in the film, offered this assessment:

At first the terminology and the concept were so complicated and dry to me, but the way Adam McKay presents it is so funny and entertaining. He breaks down the complicated theories and makes it understandable and accessible. I hope people will learn more about it so it creates a discussion.

We instructional designers hope that the learning experiences we create will garner similar reactions from our learners. Now, Adam McKay is not an instructional designer by trade. He’s a film director and screenwriter. Nevertheless, The Big Short adopts some pretty solid instructional design principles. Here’s a brief analysis of each and some ideas about how to use similar strategies to make Oscar-worthy training.

1. Explain concepts at the moment of need.

Information overload.

A viewer has to understand about half a dozen financial terms to really follow The Big Short and the implications of its dialog and plot. Rather than explain concepts like tranche and synthetic CDO up front, The Big Short elucidates them with short scenes, pauses and narration, inserted in thin slices throughout the film.

Imagine if all these financial terms were explained before the opening scene, perhaps in a 10-minute mini-lesson in finance delivered alongside the opening credits. Would an audience be inclined to pay attention to this content? Perhaps, but it’s unlikely. It wouldn’t be clear to viewers how the concepts apply to what is really interesting to them—the drama of the story.

When learners don’t immediately grasp the importance of new material, they tend to tune it out. That’s why it’s often better to explain foundational concepts within a scenario or performance context. The desire to understand a story or complete a challenging activity motivates learners to pay attention to any information that is required for achieving that understanding or completion.

Alas, training departments don’t have Hollywood budgets. Fortunately, a host of tools and strategies is available for delivering information at the moment of need: job aids, tutorial videos, hyperlinks, popup boxes, and instant messaging are just a few of these.

2. Use familiarity to capture attention.

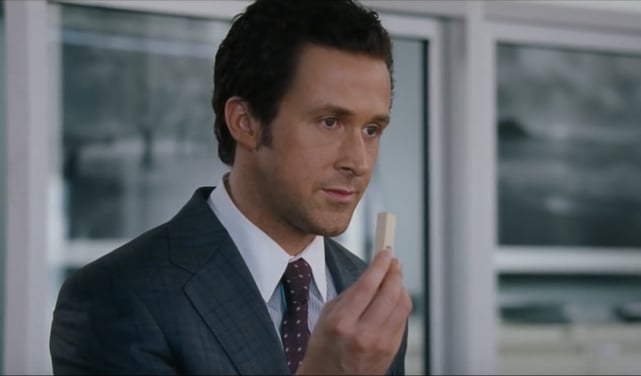

Star power + Jenga metaphor = a comprehending audience.

The presence of celebrities make the brief explanatory scenes I described above more powerful. We humans have a tendency to pay attention to familiar faces; they’re what learning interface expert Dorian Peters calls a “primal attention grabber.” Furthermore, these celebrities often appear suddenly in The Big Short, creating a feeling of delightful surprise—another attention grabber. In one iconic scene from the film, Ryan Gosling uses a modified Jenga set to explain the basics of mortgage ratings. (Here’s a YouTube link to the scene. There’s some profanity, so you’ll want your headphones handy.) Other such mini-lectures feature Margot Robbie in a bubble bath, Anthony Bourdain cooking fish stew, and Selena Gomez playing blackjack with economist Dr. Richard Thaler.

Of course, a lecture on mortgage-backed securities is going to be more captivating when delivered by a person covered in bubbles, but we’re not going to use such imagery in our corporate training materials. Nor, I imagine, will we be able to get Brad Pitt to star in our new hire orientation videos. Yet the key is not really celebrity, but the feeling of recognition. Even if we instructional designers can’t hire Hollywood stars to grab learners’ attention, we can achieve similar benefits by using photos and videos of real employees and business leaders in our training materials.

3. Leverage a compelling narrative.

In The Big Short, facts and statistics about the economy are delivered via dialog.

A storyteller constructs a narrative in order to elicit cognitive and/or emotional responses from the listener. This is also true for other storytelling media, such as films, novels, comics, and video games. Engaging with a story involves thinking critically about the plot, the characters, and the surrounding circumstances. We analyze the details of setting and dialog to understand what has happened and predict what will happen next. Narrative has always been used to instruct as well as entertain, so I think of storytelling as the original form of instructional design.

The instructional goal of The Big Short was to educate consumers about the roots of the 2008 financial crisis. Before the picture was released, there were already dozens of films and documentaries about the crisis, in addition to millions of web articles and hundreds of books, including the Michael Lewis bestseller on which the film was based. So why make another piece? Well, people love an underdog story. A blockbuster about “a handful of unlikely—really unlikely—heroes” might garner a wider audience than even the most well-reviewed documentary, and result in greater instructional impact than films that didn’t feature such captivating characters.

Storytelling may be entertaining, but it’s not always the most efficient or effective way for people to acquire new knowledge or skills. Narrative might be an appropriate way to:

-

Model a process or behavior. Stories can help learners interpret and remember best practices. For example, as part of their onboarding experience, new call center employees might listen to a tenured agent recount their experience when working with an angry customer.

-

Impart wisdom or inspiration. Keynote speakers often relate stories to inspire others to act or think differently about a topic.

-

Practice creating stories. Many jobs involve an element of storytelling, including sales and instructional design.

-

Communicate values. It isn’t enough to tell new employees that the company “cares for the environment.” Learners need to see how values are represented in the actions of employees, and stories provide an effective means of doing this.

In writing and directing The Big Short, Adam McKay faced challenges quite similar to the ones we regularly face as instructional designers: making specialized knowledge interesting and applicable, getting people to engage with a topic, and helping them understand and care about past events. If the Academy Awards had a category for Best Instructional Design, I think The Big Short would be the leading nominee.

LIKE WHAT YOU'VE READ? SHARE THE KNOWLEDGE WITH YOUR PEERS USING THIS READY-MADE TWEET!

CLICK TO TWEET: Three Solid #InstructionalDesign Principles in @thebigshort http://hubs.ly/H01TTKL0 #aiblog @customelearning

About the Author: Ellen Burns-Johnson

Ellen Burns-Johnson has over a decade of experience in the education and training industries. She has crafted the instructional strategy and design for dozens of major initiatives across diverse topics, from classroom safety to IT sales. Emphasizing collaboration and playfulness in her approach to creating learning experiences, Ellen’s work has earned multiple industry awards for interactivity and game-based design. Ellen is also a Certified Scrum Master® and strives to bring the principles of Agile to life in the L&D field. Whether a client is a Fortune 100 company or a local nonprofit, she believes that the best learning experiences are created through processes built on transparency between sponsors and developers, empirical processes, and respect for learners. Outside of her LXD work, Ellen plays video games (and sometimes makes them) and runs around the Twin Cities with her two mischievous dogs (ask for pictures).

Comments

Would you like to leave a comment?

Related Blog Posts

By: Ellen Burns-Johnson | Feb, 2020

Category: Custom Learning

Blog

Three Tips to Avoid the “Dark Side” of Microlearning

By Ellen Burns-Johnson, Instructional Designer / @EllenBJohnson The Big Short is a recently released dark comedy that explores the 2008 financial ...

By: Ellen Burns-Johnson | Aug, 2016

Category: Custom Learning

Blog

Oh What a Feeling: Emotion and Learner Engagement

By Ellen Burns-Johnson, Instructional Designer / @EllenBJohnson The Big Short is a recently released dark comedy that explores the 2008 financial ...

By: Ellen Burns-Johnson | Oct, 2014

Category: Custom Learning